Lucian Camp is a financial services brand consultant, copywriter, author and blogger. He co-presents the On The Other Hand podcast.

I read a great quote in a newspaper article this morning. Someone called Neil Stead, who’d been involved some years ago in setting up Waitrose’s customer loyalty programme, looked back on the way they’d approached it. “It’s not about our customers’ loyalty to us”, they’d told themselves, “it’s about our loyalty to our customers.”.

I silently cheered over my toast and marmalade, and I think I may have cheered out loud, just quietly, when he went on “By investing in your customer, you drive longer-term loyalty, value and profit.” This seemed to me exactly and precisely the right way of thinking about loyalty programmes, and indeed about the subject of customer loyalty as a whole. And of course it’s diametrically, 180 degrees, unlike the way most organisations and especially most financial services organisations think about the subject.

Actually, I would say that in many parts of financial services, the difference is more than 180 degrees, were it not for the fact that degrees don’t work like that and if it was more than 180 degrees it would be doubling back on itself to return to the starting-point more quickly, if you see what I mean. Left to their own devices, many firms of all shapes and sizes prefer to punish customers for their loyalty, overcharging them as ruthlessly as they possibly can. It’s good to know that one of the most egregious examples – general insurance companies massively ramping up the premiums of customers stupid enough to stay with them – came to an end some 18 months or so ago. But less good to know that it only came to an end because the regulator banned it, not because the firms had a flicker of remorse, and anyway apparently there’s some sort of loophole that means they can largely get around the new rules.

There are plenty of other examples of the same or similar strategies to gouge firms’ most loyal customers – asset managers, life companies and advisers, despite token efforts at disclosure, trousering huge annual fees for next to no work, banks charging for packaged accounts with little or no real value, mortgage lenders with lead-in rates for new customers only, the list goes on.

But the real insult-to-injury kicker is that so many firms up to their necks in this sort of manipulation somehow still manage to believe they have a right to their customers’ loyalty. It literally hasn’t occurred to them that loyalty, in business just as in real life, is a two-way street. If they want me to show some loyalty to them, the best way – arguably the only way – to go about it is to start by showing some loyalty to me. And, of course, that’s where the comments made by Neil Stead at Waitrose come in.

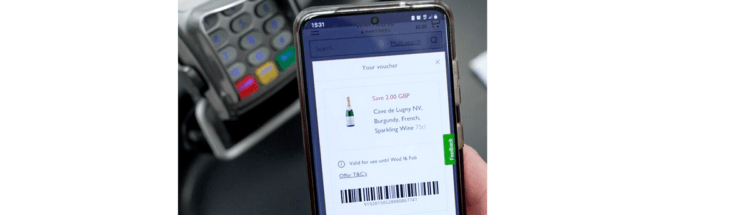

The MyWaitrose scheme went a good deal further than just resisting the temptation to steal their loyal customers’ money. It also included some genuinely valuable benefits, like free in-store coffees and newspapers even when loyal customers spent remarkably small sums. And vouchers entitling us to real savings on the cost of our shopping. And I remember other vouchers exchangeable for more free coffee and also cake at cafes in any branch of John Lewis, although I did notice the copy about the cake was carefully (and not unreasonably) worded to allow me to enjoy a slice but not to walk off with the whole coffee-and-walnut or lemon-drizzle confection.

You may wonder why I’m writing about MyWaitrose in the past tense, not the present. It’s partly because I think I’ve heard that in today’s troubled times, Mr Stead’s generous scheme has become Mr Stead’s rather over-generous and extravagant scheme and has been trimmed back quite a bit. But also – I’ll be honest – it’s because all those coffees, cakes, newspapers and vouchers weren’t enough to keep me loyal. Come the cost of living crisis, I traded down to Sainsbury’s, and I reckon I’ve saved about 25% on the cost of the weekly shop.

Well, I loved the way that Waitrose showed me such loyalty. But that didn’t mean I’d given up my right to behave like an ungrateful bastard.