By Michael Bernard, Co-founder of House of Strategy

Can one imagine a good quality marketing strategy that is not underpinned by a strong sense of purpose? Nope. Can’t do it.

What do we mean by ‘purpose’? In his book ‘Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us’, Daniel Pink sees it as one of the three key employee motivational forces, along with mastery and autonomy. It has a strong psychological impact, but more importantly, it is the most fundamental basis for building strategy, along with vision and mission. Without it, there is little chance that an organisation or a function, like marketing, will be able to discern which of the many choices that could be made are likely to be right.

Purpose is usually captured in a purpose statement. Many people sigh when they see one. If done poorly, it is a dull and uninformative statement of the obvious. However, well-crafted purpose statements shed genuine light on what an organisation exists to achieve.

Let’s look at an example: Tesla’s purpose is “to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy”. Note that they call it their mission, which is often confused with purpose, but that’s for a separate discussion. What makes their statement interesting is that it explains how a car company also has a grid battery division and a solar tile and domestic battery business. Tesla understands its purpose very clearly and that means their marketing, as well as product development, acquisitions and hiring reflect their purpose. There was a huge fuss when Tesla briefly accepted bitcoin in payment for cars, because bitcoin generates huge amounts of greenhouse gases from mining. The dissonance with the purpose quickly meant that decision was reversed.

One major UK bank, for example, has a lengthy purpose statement of four paragraphs, in which it claims that it is focused on sustainability. This same bank is the focus of numerous protests for its loans to fossil fuel companies and for oil and gas infrastructure. A marketing strategy is always going to be hampered by a company that is perceived as not living up to its stated purpose.

A good purpose statement may well be the longest lasting construct of a company. Its goals, mission, products and offerings, leaders and employees may change while the purpose will remain consistent. This means the purpose must not tie a company into one product or product set. The clear danger of doing that is the ‘Kodak effect’, where photographic film was so embedded in their culture that they were too slow to move to digital.

Assuming that marketing is the corporate ‘owner’ of a brand, then there has to be a strong relationship between purpose and brand. Again, differences between the two will mean that the organisation comes across as uncertain of itself. It will not feel ‘authentic’. The brand strategy needs to sit alongside the marketing strategy, but they should be understood as complementary, not identical. Look at how the best companies manage their brand. My personal experience is that Apple, for example, is fanatical and highly detailed at how each part of their branding is handled. They realise that their ability to charge a premium is intimately related to their strong brand. Their purpose statement is “to bring the best user experience to its customers through its innovative hardware, software, and services.”

This means that their marketing strategy must also focus on bringing the best user experience to every interaction with Apple, including social media, advertisements, landing pages, response and complaint handling, lead management – whether that is done by Apple directly, or performed by its many business partners.

If you consider your own marketing strategy, how would you assess how the purpose, vision and mission have informed every part of that plan? Does every element of your plan reflect the purpose (and brand) of the company that you represent?

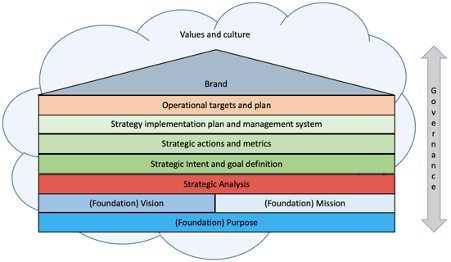

It is clear, therefore, that the foundations of good st rategy are purpose, vision and mission. The concept of the ‘house of strategy’ depends on these foundations:

- Purpose explains why the organisation exists

- Vision paints a picture of what the world and/or the organisation will look like should that purpose be fulfilled.

- Mission is the direction the organisation sets to deliver its purpose.

Once these foundations are firmly in place, then the rest of the house can be built without fear that it will fall down at the first hint of bad weather.

The marketing strategy then needs to have a clear sense of the purpose of the marketing function itself. Why does the company employ marketers and not simply engage with an agency who can come up with the marketing strategy, content and campaigns? Combine the understanding of the company’s purpose with the clarity about what marketing is there to do, and you have a good start.

My previous employer, IBM, had a purpose built around the enduring idea of ‘world-changing progress’, together with being ‘essential’ to its customers. This informed all marketing activities, no matter whether for hardware, software or services. Not only did it mean that the marketing plans and activities for each division stressed the ways in which it could help clients to transform their businesses, it meant that there was a high degree of consistency between the marketing strategies of all parts of the company.

Other key elements of a marketing strategy can then be put in place: a vision of how the clients will be served after this strategy is executed; a clear set of goals; the strategic analysis that lays out the current environment; the strategic intent stating what will be done by marketing to meet the goals; the strategic actions in line with the intent; the route(s) to market design; lastly, the measurements and management system.

The conclusion is that a marketing strategy – or any strategy, for that matter – must be underpinned by the organisation and functional purpose. Without this bedrock, the strategy will be much harder to create; it will not survive detailed inspection; it may clash with the organisation’s brand and will appear disconnected to those it seeks to persuade.

About the author:

Michael Bernard has many years of experience producing business and marketing strategies for IBM and is the co-founder of strategy consultancy House of Strategy. He is also a non-executive director, trustee, school governor, board advisor and consultant. Michael specialises in helping organisations produce strategies that are innovative, effective and suit their unique values and ambitions. Over his career he recognised that people commonly made the same mistakes when writing strategy, and he aims to help people move beyond prescriptive strategy formulas to create strategies that are both ambitious and effective.