The face of financial advice is about to change again. Parts of the new régime may sound familiar, but Claire Labrum warns that the consequences could be far-reaching.

Independent financial advisers (IFAs) have traditionally worked rather like a cottage industry: a disparate collection of individuals with widely-divergent working styles and practices, brought together as a result of force of circumstance. This is still the case, and it is very difficult to talk collectively (although most people do!) and meaningfully about the IFA market and the views and opinions of its members.

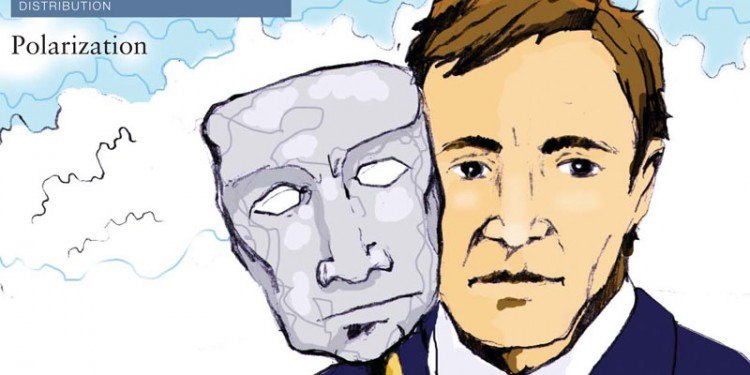

However, the recent regulatory changes (depolarization in particular, but also the low-commission environment), as well as the creation of the Personal Finance Society (from the merger of the Life Insurance Association and the Society of Financial Advisers) may herald the emergence of this collection of “advisers” into a more coherent, organized and professional sector – one that can perhaps rebuild consumer trust (currently at an all-time low); be much more responsive to criticism (preventing, for example, a repetition of the slow progress on the second phase of pensions mis-selling restitution); and have a single and coherent lobbying voice.

But what do all these changes mean for individual advisers and their relationships with the providers?

Second wind

The IFA market is currently going through its second major upheaval – which seems to be taking the industry full circle to where it first came from! The independent financial adviser was created by the Financial Services Act 1986, which was introduced partly because of increasing concern about several high-profile frauds, and more general concern about – at best – inappropriate selling. One of the key decisions was to “polarize” the market between IFAs (required to recommend, under “best advice”, the most suitable product from the whole range of providers in the market) and “tied agents”, able only to recommend the products of the company to which they were tied.

Before this, anyone could call themselves a broker and claim to be “independent”, and then sell life and pensions products, with no requirement for formal training or any disclosure to the client of the remuneration that would be received from the product provider. Historically the system had appeared to work reasonably well for most people – but that was scant comfort for the minority that had been very poorly served. There was also real concern that the scale of abuse might escalate, as the industry was forced to recruit large numbers of new brokers to cope with the effects of the huge growth in the housing market and moves to popularize personal pensions.

In many cases, the relationship between the life company and the independent broker was everything

The broker would be schmoozed by the life company inspector, and business would begin flowing in. As long as the products and prices were not absolutely dire, generally it was a case of the more schmoozing, the more business. The quality of that business was of little importance – the inspector was remunerated on business won, and the broker on commission.

To read the full article, please download the PDF above.